You can ask almost anyone and they’ll tell you it’s true: The skilled trades has a workforce shortage.

A March report from Washington state group PeopleReady Skilled Trades found while available apprenticeships and jobs in sectors like plumbing, roofing, carpentry and construction were increasing, sometimes as much as 50% within a month, postings were unfilled for a month or more.

In Mass., this shortage is playing out in part in the state’s vocational-technical high schools, which are facing increased demand despite the reported shortages. According to a February presentation from a special Mass. Board of Elementary and Secondary Education meeting, some 18,560 completed applications were submitted to enroll as ninth graders across 58 vocational schools and programs in the last academic year. Of those applications, 12,454 received an offer of admission, with 9,951 students enrolled as of Oct. 1.

By those figures, only about 56% of applicants with completed applications were offered admission, with slightly less than that ultimately enrolling. In other words, according to the presentation at the BESE meeting, there were 1.75 applications for every available vocational program seat.

Such figures have fueled questions about exactly who gets admitted to the state’s highly sought after vocational programs, what the rules are for applying, and what those students will do once they’re done matriculating. In response to primarily the former, BESE approved on June 22 amendments to its regulations regarding vocational admission procedures, loosening admission criteria and requiring schools to actively work to make sure their admissions policies include strategies to attract and enroll a student body, which has a comparable academic and demographic profile to the towns from which the vocational schools pull students. In short, the new rules lessen the requirements for academic excellence.

The changes have divided stakeholders in the state’s vocational-technical education programming, some of which say the changes have not gone far enough – arguing in favor of a complete lottery system not prioritizing academic superiority or social status, and others who say students who are academically strong and interested in taking their vocational training on to college shouldn’t be barred admission for doing so.

Workforce development

“It’s frustrating and I think it finally came to the point where something’s gotta be done,” said Jeannie Hebert, Blackstone Valley Chamber of Commerce president and CEO and the force behind the Northbridge-based Blackstone Valley Educational Hub. “They’ve become elite schools, and that was not what was meant to be.”

Hebert said vocational schools have fallen from their original intent. Such programs were meant to teach students who weren’t academically stellar but who were interested in learning trades, including those students who have learning disabilities and other special needs.

Indeed, economically disadvantaged students and students with disabilities attend vocational schools at slightly higher rates than they do statewide, per February’s report. However, in 2020, students of color attended vocational schools at a rate of 39% compared to 43% of schools statewide. English language learners attended vocational schools at a rate of 6%, compared to 10% across the commonwealth. The same BESE presentation indicated both students of color and English language learners apply to vocational schools at lower rates than their counterparts, with fewer acceptances and enrollment.

College rates

While vocational-technical schools have in some cases become magnet institutions, their occasional penchant for academic excellence has made them vulnerable to criticism their priorities are in the wrong place.

The tension creates a double-edged sword: no one wants students at vocational institutions to fail, per se, but some argue excellent academic track records miss the point.

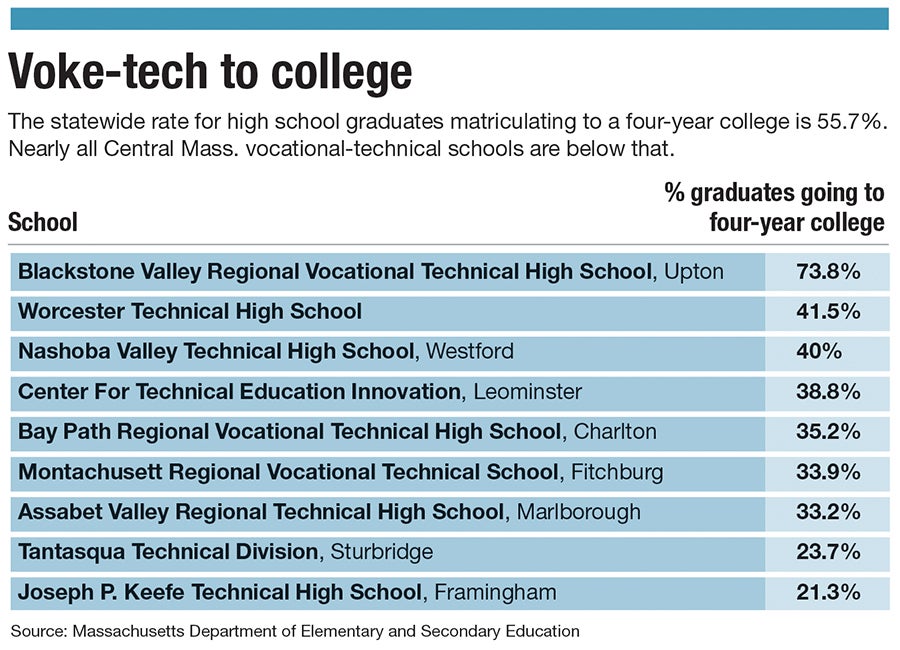

At Blackstone Valley Regional Technical High School, the only vocational school in Central Mass. sending students to college at a rate higher than statewide figures, the student body graduates at rates as high as 100%, with the lowest graduation rate recently recorded coming in at 98.4%, according to the school’s 2020 District Report Card, maintained by DESE. Statewide the same year, graduation rates were 88%.

At the same time, 78.7% of its 2019 graduates enrolled in post-secondary education programs, compared to 72% of students statewide, with 73.8% of students attending a four-year college, compared to 55.7% of students across Massachusetts.

Worcester Technical High School also enjoys a higher graduation rate than high schools statewide, with 98.4% graduating in four years in 2019. However, students at Worcester Tech do not attend post-secondary education programs at higher rates than students who graduate statewide. In 2019, 64.2% of graduates continued their education, with only 41.5% going to a four-year school.

Timothy Murray, president and CEO of the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce and former lieutenant governor, doesn’t think the onus is on vocational regulators to take issue with students who choose to take their vocational training and attend college, versus directly entering the workforce.

“We can do both,” Murray said. “We can walk and chew gum.”

More people are going to college across the board, he said, and instituting a lottery would still leave applicants rejected from vocational programs.

From his vantage point, the most important step to remedy waitlists and boost the trades workforce is to expand vocational programming, both through building new schools and by adding vocational-technical training opportunities to schools. The latter is especially useful, he said, when comprehensive high schools add programs that complement, rather than compete with, their local vocational school.

“Any kid or family that wants access to a Chapter 74 program should have it because it’s the way of the future,” Murray said.

Although stakeholders vary on whether they think it’s appropriate for vocational schools to graduate a high number of students into college, most everyone agrees vocational programs should be expanded, in general, whether through building new schools, public-private partnerships, hybrid programs like Blackstone Valley Ed Hub, which offers training to more population groups than just high school students, or through adding on to preexisting comprehensive schools.

“There’s obviously a challenge here, with bringing high-level education, which we know vocational education is. We’ve seen the success of the vocational schools,” said Jeffrey Turgeon, executive director of the MassHire Central Region Workforce Board. “So the challenge is how do we expand that?”

At the end of the day, the goal should be bringing the opportunity to have vocational training to those who want it, which could then reduce waitlists at local schools, Turgeon said.