Around this time last year, America’s manufacturing industry was thrust into the fight against the deadliest pandemic in a century, including a little-known Hudson maker of elastic products.

United Stretch Design Corp., located in an unassuming warehouse in an industrial park off of Route 62, became one of those industrial heroes of the COVID-19 pandemic when the company produced millions of yards of elastic used on facemasks to help prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

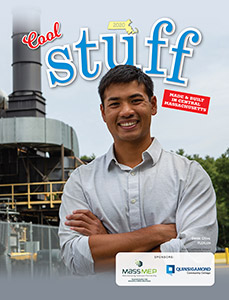

“Thankfully, we were able to keep everybody employed,” said Eric Chaves, operations manager and son of President and Founder Manuel Chaves. “In fact, we were working Saturdays and Sundays around the clock.”

Chaves arrived in the U.S. on a Friday, and started working on a Monday.

After learning the ins and outs of the manufacturing industry, Manuel started his own business using three machines to make elastic cord.

Now, the company has around 1,500 machines and makes a variety of products, ranging from flat elastic used in the pocket in back of car seats to braids used on military uniforms. The company also produces shoelaces, hockey skate laces, and zipper pulls.

“Braided and textile products are everywhere,” he said. “It’s usually a smaller component of something that you don’t really ever pay much attention to.”

The company had already been making the flat elastic bands for facemasks well before COVID, but it was never truly a core business. On an average week, United Stretch Design would produce about 40,000 yards of the product.

When COVID-19 hit, the company kicked it into high gear, and that number grew nearly 700% to 300,000.

“If we could have made 3 million yards, it wouldn’t have kept up with the demand,” Chaves said.

The company kept a healthy rotation of workers to keep the machines running, and even brought in some outside help to keep employees fresh.

“There were a lot of those people,” Chaves said.

With the supply of masks caught up, the company has slowed its production of that elastic, but is still pumping out about 150,000 yards a week.

That rush, however, helped the company become more efficient.

“We literally couldn’t afford to have a machine down,” so we had to be a couple steps ahead of that, Chaves said.

“We worked overtime – a lot, a lot of overtime,” Chaves said.